Tripoli

Nope, not Gaddafi’s capital, this coastal city is the Mecca of Middle Eastern sweets. Baklava & other halawiyat galore.

News and vignettes

Nope, not Gaddafi’s capital, this coastal city is the Mecca of Middle Eastern sweets. Baklava & other halawiyat galore.

Unlike the camp I had seen in Beirut yesterday, the roads leading into the Al-Baas Palestinian camp were blocked by large concrete blocks, and on the principal roads, Lebanese army. I couldn’t help wonder if the scooters that nipped past were keeping tabs on me here.

The prevalence of Fatah in Sabra & Chatila was contrasted here by that of Hamas. Speaking with one guy in the street, he told me he was Hamas, but that his cousin who stood next to him, was affiliated with Fatah. “Is this a problem?” I asked. “Not here” was the reply. In Palestine, yes.

Later on, drinking tea in a family home, several framed photographs hung on the wall. One depicted my host in his Palestinian army unit, each of the men in red berets yielding Kalashnikovs. Another showed a famous Palestinian general, and another, Yassar Arafat.

The opposite wall held family photographs. There was a photograph of him shaking hands with his brother, but a barbed-wire fence separated them. He stood in south Lebanon, his brother in Israel, although he referred to it as “Palestine”. This was the first time they’d seen each other in years, but their meeting was marred by metal.

His son had graduated as an engineer, but the opportunities for Palestinians here are somewhat more constrained than their Syrian counterparts. He had a job, which is difficult enough to find — there is heavy discrimination — but no chance of a contract, and therefore no job security. “Just the pay-check at the end of the month”, he said.

A storm was sending waves crashing into the Lebanese coastline as the bus battled against the wind, strafing the coast from Beirut to Sidon and Sidon to Tyre. Between this coastal road and the sea, the palms of the banana plantations were outstretched to the bus, seemingly clinging on to their branches as the wind tried to rip them from each other. Further south, the the finer leaves of the citron groves fared slightly better.

The Roman columns in Tyre jut out into the sea. The setting seemed a million miles away from that of the long colonnade that I had seen in Apamea. Next to this site stood a Muslim cemetery. Many fresh headstones bore the photographs of young “martyrs”; this city has sacrificed much of its youth. The yellow flags of Hezbollah adorned many of the graves, and Fatah and Amal were well represented, too. The violent struggle of this town was reflected as wind whipped the long, black flags lining the beach.

The presence of the United Nations Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIIL) were testament to this. Their checkpoints stationed along the road between Sidon and Tyre, and many troops are stationed in the town.

On the way back north, the small mini-bus in which I traveled was stopped at a Lebanese army checkpoint. The driver was questioned a lot, and not happy about it. He explained that this vehicle provides the income for three families. Three drivers are assigned “shifts” driving the vehicle, the money they earn being the sole support for each of their families. If the vehicle is removed, it blows the livelihood of three whole families. A rough mental-arithmetic of the fares & journey-times put that income at around $40 a day, and then from that one must deduct the petrol costs & servicing of the vehicle.

Wandering the back-alleys of Lebanon, it can sometimes be a little intimidating when faced with the posters of the political parties & militias here.

Men in ski-masks, brandishing kalashnikovs; party logos bearing crossed arms; names such as the Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine. I find it particularly disturbing when these images are plastered on the doors of a UNRWA school. Children are growing up with this image.

But this imagery also reflect the psyche of despair in political progress. Talks come and talks go, and little real progress seems to be made.

Hezbollah has a bad name in the Western press, but following the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war, they also garnered a lot of support with the progress they made in security, and in the education and social welfare that they brought.

I direct you to a small series of some of what I saw adorning walls in the Lebanese capital.

» Click here to see the photos, though some things were “off limits”.

The British gained their mandate over Palestine (now, modern-day Israel & the Palestinian Territories) in 1922 but by 1947, one year before it ended, they had had enough. They were not able to find a solution to the integration of “a national home for the Jewish people” in the region, and during the mandate period, had faced revolts by both the Arabs and the Jews.

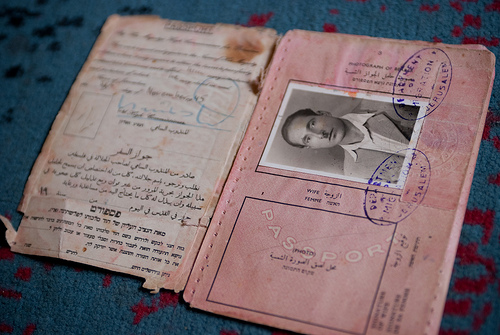

Whilst in the home of a Palestinian family in the Beirut Palestinian camp of Sabra & Chatila, I was shown a passport that the family had kept from their father. I found this document incredible. I had heard of Palestinians keeping the keys of the homes they had fled in 1948, on the creation of the Jewish state, but I hadn’t thought of the documents that were issued during the period of British rule.

I was asked if with this document, it gave them, the children, and now grandchildren of its bearer, the right to immigrate to the UK, but reading the small print in the back of it, this was not the case.

The passport was issued in Jerusalem, and printed in English, Arabic and Hebrew. It bore the stamps of arrival in Lebanon, newly independent after the French mandate of Lebanon & Syria.

The preamble to the passport is practically identical to my own, current, passport:

By His Majesty’s High Commissioner for Palestine.

These are to request and require in the Name of His Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance and to afford him every assistance and protection of which he may stand in need.

The Palestinians of Lebanon now have little chance to “pass freely without let or hindrance”.