Days of Tea

I had time to kill in Khartoum, and so took to the streets. Ostensibly, it was the election prolongation that was keeping me here, but in reality there were a few more factors. An increasing interest in the country, particularly at this time in Sudan’s history; a growing social group of people whose company I valued; perhaps also the need to take a little repose from traveling.

Khartoum is perhaps a strange place to do this. There is very little in terms of things to “do”, particularly as a new arrival; I had already visited the two main museums, the National museum and Ethnographic museum. There are no cafés boasting taawila as in Cairo, nor the Egyptian capital’s bustling cultural scene. Khartoum is a long way from Damascus’ architectural grace and Jerusalem’s historical significance. Furthermore, the climate is incredibly oppressive — daytime temperatures stay above 40°, the streets are dusty and walking them is an arduous affair.

Yet this is what I did. I walked across the city to the soundtrack of shouts of khawaaja (the affectionate, Sudanese equivalent of mzungu or “foreigner”). Life in Sudan is lethargic, with many people seemingly just sitting around or snoozing, taking shelter from the sun.

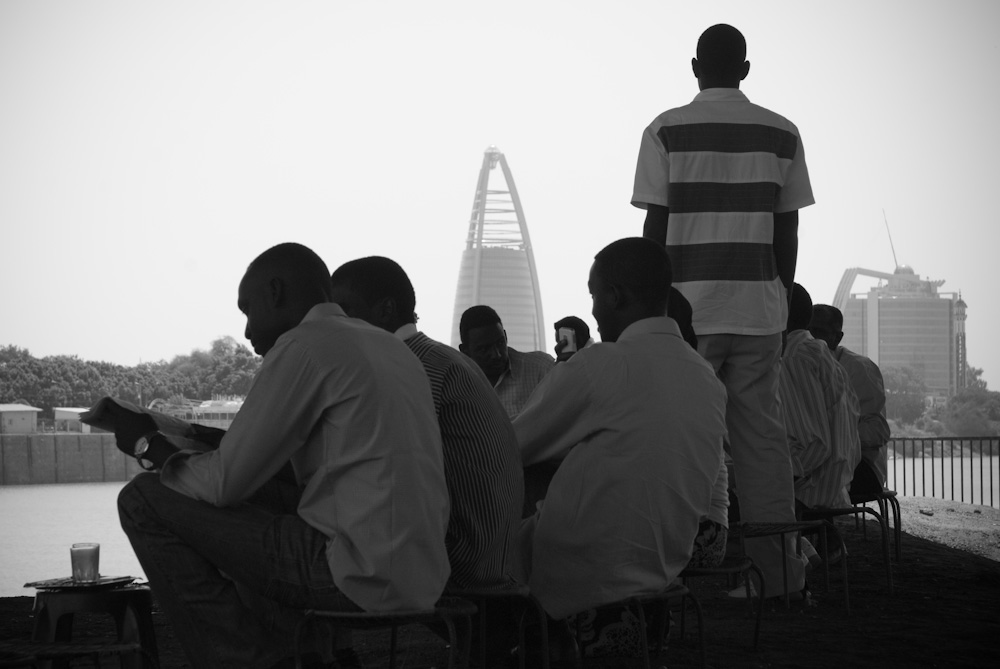

I stopped frequently to take jebbaneh — coffee spiced with ginger — or a shai bil-nana — tea with a little mint. Whilst there is a lack of cafés, there is certainly a plenitude of tea-ladies plying their trade, and this is the place to meet people. The Sudanese are incredibly friendly and keen to speak to khawaaja about their country, for which they often feel great pride, and find out what the said khawaaja thinks about it. At times frustrating, being asked for the umpteenth time about the difficulty of the heat, but often enlightening, discovering more about this confused country’s culture.

Admittedly, language often limited conversation; my Arabic is far from capable of holding a meaningful conversation and in many of the places I took refreshment, English was not in abundance. A half-built building opposite the University of Sudan changed this situation. In its concrete shell seemed to exist an impromptu Students’ Union, full of people sat around on small, rope-twined stools surrounding tea-ladies.

The students here were keen to discuss Sudan. Some were waiting for the first opportunity to emigrate and make their life in Europe, others had aspirations to develop the country and make change here in Sudan. Some felt exasperated at the limited opportunities they have, explaining that without being a member of the ruling National Congress Party, jobs are hard to find; Western countries are less than forthcoming with visas for Sudanese nationals. Ahove all, this trip has made me realise—and cherish—the value of my passport, and the luck I had in the nationality lottery…