Sabra & Chatila Palestinian Camps

Looking over West Beirut at sunset from the fourteenth floor of St. George’s Towers, seeing the new high-rise blocks and the floodlights of the Camille Chamoun stadium rising in the skyline next to Sabra & Chatila, it’s hard to imagine what it would have looked like 28 years ago, when columns of smoke would have been climbing into the sky under the incessant Israeli shelling.

I got a little obsessed with a book by Robert Fisk whilst I was in Lebanon. I was up until the wee hours every night, reading Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War, learning about the events that passed here, and how this one journalist witnessed it all.

In his book, Fisk often refers to the Beirut districts of Sabra & Chatila, the now infamous Palestinian refugee camps. Long before the massacres — led by the Christian Phalangist militias — they bore the brunt of the Israeli shelling & air-raids on the city. Arafat had his PLO headquarters based there.

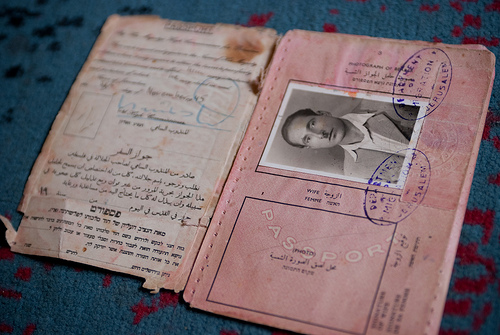

Twenty-eight years after these events, I spent the afternoon in the camps, their borders now somewhat blurred. I had spent time with Palestinians in Syria and in Jordan, and now I wanted to see how life compared for those living in Lebanon.

There is still violence in the camps, although nowadays the danger comes from the friction between the Lebanese poor — whose shanties border Chatila — and the Palestinians. Every night, I was told, there is gunfire and “bombs” (although I suspect that the “explosions” are from somewhat smaller arms). Talking with people, I discovered that the night before I arrived, two Lebanese men had been fatally shot. News of this didn’t really make it out of the camp.

Walking into the area from the south, I first crossed a neighbourhood controlled by Amal, the Shi’a militia movement. Not far down the road, it is Hezbollah who control the streets. I sat for a while with two guys, talking about life here. Diib, the “boss” of this little quarter, says he wants to get out. “Fuck Lebanon.” He is fed-up of the poverty and the violence. As he says this, he pulls out a flick-knife and chases off a guy who took a liking to my watch and who talked back to him.

As I walked north towards the Palestinian camp, he advised me not to go there. “Dangerous people”, he said. Talking with Palestinians in the camp, they had the same advice about going south, back down to the Lebanese.

I was led-up onto the roof of a block of apartments, from which the expanse of the camps was pointed out. He indicated that this was Palestine. In the streets, posters of Arafat are ubiquitous. Opposite, lay the huts of the Lebanese. The concentration of people in this small area is astonishing. Drinking tea back in an apartment, the electricity often cuts out.

But the atmosphere here, particularly along the main street, is lively. A fruit & vegetable market is bustling with people, and in a small street I sit in a small canteen opening out onto the street, watching the life of the quarter. Whilst the old lady running the place was surprised to see me here, a Westerner ordering a bowl of fuul, she was very welcoming and happy to see me here. No, I was not an aid worker, nor a journalist. I am just here. “Bravo”, she said.

Some days later, I re-watched Waltz With Bashir, the acclaimed Israeli documentary/film that treats the events surrounding the massacre. Whilst it has been criticised for down-playing the Israeli/IDF involvement in the killing of so many innocents, the depiction of certain parts of what I now recognised in Beirut was disturbingly accurate.

» See more photos from Sabra & Chatila.