Autoportrait — Hell’s Gate

Looking out over Ol Njorwa, I couldn’t resist. It’s been a while, and the series continues.

News and vignettes

Looking out over Ol Njorwa, I couldn’t resist. It’s been a while, and the series continues.

It felt good to be out in nature again. Hiring mountain bikes and taking them for a spin as warthogs scuttled in the long grasses beside the track. I couldn’t help but thing of pumbaa in the Lion King, and sing to myself “…when I was a young warthog…”. Sad, I know.

As you enter the national park, a column of rock—Fischer’s Tower—rises out of the plains. I had to have a boulder around, despite wearing heavy hiking boots and soloing up a little too high. It felt good to touch rock again. I am starting to realise I miss certain things…

At the other end of the national park the earth opens up and one can descend into the Masai land of Ol Njorwa, the Lower Gorge. The change in landscape is dramatic, as hot water seeps out of the rock in this area of geothermal activity. Walking through with a Masai guide from the local community, he points out the plants that provide natural remedies.

Riding back from the park to the camp, the road is lined by small children from the flower-growing communities that have sprouted up here. “How are you? How are you?” choruses out as we cycle past. Two days ago I was in another world.

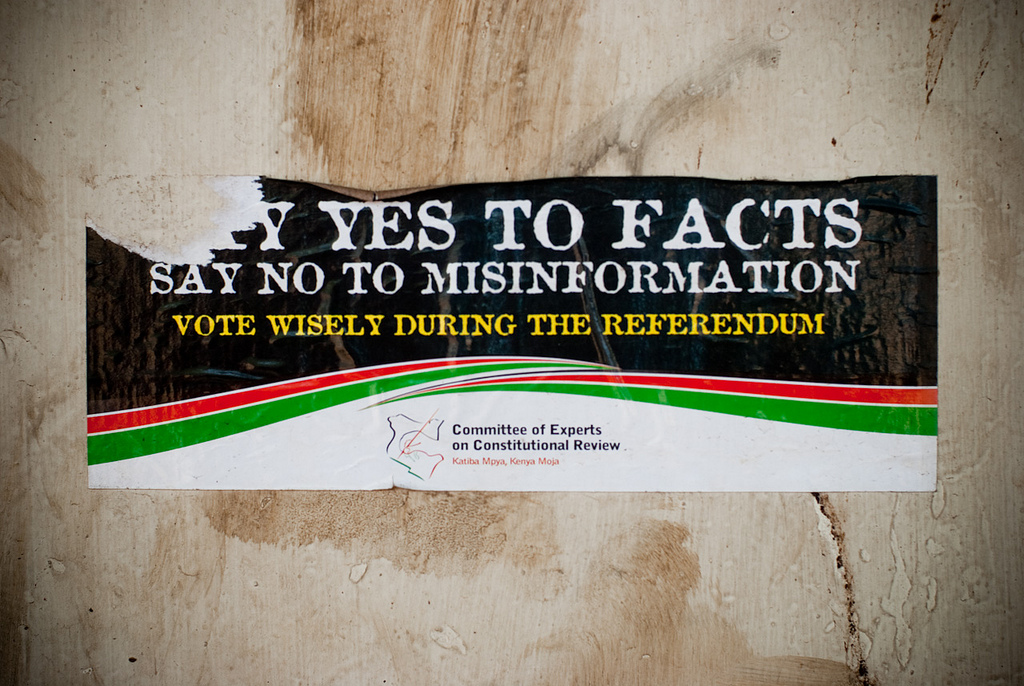

I have a knack for arriving in places as key events are going on. The day after I touched down in Nairobi, Kenyans were voting in a referendum to change their constitution; it has not really changed since the one agreed in 1963, following their independence from British colonial rule.

I had come straight to the Rift Valley, which turned out to be the prime ground for the “no” vote to change. It’s not that they opposed changing the constitution, but felt that the proposed one did not go far enough to address issues. Al Jazeera reported that several hundred people fled their homes prior to the vote, fearing violence. The Rift Valley saw some of the worst of the post-election violence in the 2007 elections.

But speaking to people here, they were excited about the opportunity for change. One guy in a Nyama Choma joint (a typical Kenyan “roasted meat” eatery)—who had celebrated with several pints of Tusker—spoke of how this would “change his life”. There would be no more fear of the police, random stops and arrests without charge. No more bribes to pay. Corruption is a big problem, and a big deal in Kenya. The Guardian reported it with a line:

“It will end corruption for ever” … At one stroke tribalism will end, and brotherliness will reign.

— Wanjiku is ready for a new political dawn, the Guardian

People of all age, and all backgrounds were discussing it. And the television screens that night broadcast ever-changing pie-charts and updates to the tallies. Rift Valley would be the only province to vote against this constitution change, two-to-one against, but throughout the rest of the country, it was supported. Sixty seven percent of Kenyans voted “yes”. And so history was made in this East African nation.

Straight from the airport to Nairobi city-centre, passing giraffes and zebra en-route as the taxi sped down the highway past the Nairobi National Park, and then bundled into a matatu with two Australians I had met at the airport. My departure from Sudan was rather last minute, I had bought my ticket the day before, and hadn’t really read a thing about the country. I didn’t even know where, or what, Naivasha was.

But after a bumpy ride there, crammed in with ragga music blaring, we got out and found a camp. The hills rising from around the lake, I realised how much I had missed this kind of landscape, and climate. It felt strange, not to be constantly dripping with sweat. I felt cold at night; I hadn’t been cold for months. Monkeys bounded around the wooden camp buildings, and at night, hippos would wander up from the shore. La pièce de résistance, cold bottles of Tusker beer.

Crescent Island sits near the shore of Lake Naivasha, seasonally connected to the mainland, and unfortunately, increasingly so. The water levels of the lake are dropping, and the water is becoming more and more polluted. This is the region where many of Europe’s flowers are grown, and predominantly Dutch owned flower farms line the shore, their irrigation literally sucking the lake dry, along with the water needs of their thousands of employees, drafted into the region for work.

The island is a small sanctuary for wildlife, the animals initially brought here for the filming of Out of Africa, guaranteeing a backdrop of giraffe and zebra strolling about. I hadn’t planned on playing the whole safari game, the thought of being cooped up in a 4x4 driven round as meat is thrown out to entice the animals doesn’t appeal to me personally, but this was pretty cool. A small motorboat brought us from the campsite, passing herds of hippopotamuses semi-submerged in the lake, and we were left to walk amongst the wildlife, stumbling across a huge python, with gazelle, wildebeest and zebra chowing down in-between the odd giraffe. A lone tokul reminds me of Sudan. The backdrop of the lakes and the extinct volcanoes of the Great Rift Valley rising up behind them was stunning, and exactly what I needed after the four previous months.

So here’s to meeting random Ozzies at the airport.

Descending through the clouds, an expanse of green filled the window as I peered out down to the capital of South Sudan. Four hours ago I had no idea that my flight would be transiting through here, and now I wished there was a way to spend some time in the city I had spent so much time reading about during the past four months.

The contrast between the aerial view of Khartoum was striking. The Northern capital is a mass of concrete surrounded by desert. My first glimpse of Juba was a collection of tokuls engulfed in verdure. Landing, a UN helicopter sits on the runway as we taxi in. This is the land of UN agencies and NGOs.

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of 2005 ended Africa’s longest running civil war here in Sudan, and as part of that agreement, a timetable was scheduled for a referendum on the secession of the South. As part of the CPA, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the National Congress Party (NCP), the ruling parties of the South and North, respectively, were obliged to make unity “attractive” to voters. The rhetoric in Khartoum had been that they were trying this, although many people felt it was too little too late. But still, the talk was talked. Stepping off the aircraft, the first thing that alighting passengers see is a huge billboard compelling people to vote for independence in the upcoming referendum, bearing the face of Salva Kiir, the President of South Sudan and First Vice-President of the Republic of the Sudan and the logo of the SPLM. The referendum will be taking place in just over five months time, if all goes well. I want to be back here for then.

In the Juba terminal, the vibe is a very different one to that of Khartoum. The humidity is stifling, and the whole affair a lot more “rustic”. There are a few white faces in the crowd, each one screams “aid worker”.

I feared that I might face more problems with my now expired exit visa and the debacle that ensued my arrival at Khartoum airport. My fears were unfounded, and I was stamped and ushered back on to the aircraft, along with the sole other transiting passenger from Khartoum.

I expected the plane to fill with Southern Sudanese making the journey to Kenya, but as we climbed the steps from the runway, the door was closed and we taxied back to the runway. This Kenyan business man and myself had the whole of the Russian plane to ourselves.

This is the first time in my ten months of traveling that I will be crossing borders unconscious of the moment when one country changes to the next; the land between two cities an unknown.

“Welcome to Nairobi International airport, the outside temperature is 18°c” announces the pilot. “Bliss”, I think, after four months in temperatures that hovered above 40°c. I can breathe again.

Walking past the duty free shops, alcohol is once again freely available. After four months in Sudan, where the substance is illegal, it seems odd to see bottles of vodka, whisky, gin, stacked on shelves. A line of Japanese tourists stand before me in the queue for a visa, one is wearing hot-pants. This is going to be quite the culture shock after the last ten months spent in the Muslim world. Now, I just hope that they let me in. My passport expires in three months.