Juba, not the most animated of “cities”, became a bustle of foreign correspondents from the world-over during these early weeks of January 2011. The media’s plat du jour. Although when voting was over, a rather stale taste was left in the mouths of many. The circus rolled into town, and then wondered what it was doing here.

When I arrived in early December, I was issued with press card number 60. The day before voting started, the Southern Sudanese Referendum Bureau had issued around 2000. Juba was exploding with media.

What passes for a quality hotel room in Juba is invariably a container—the porta-kabins of building sites in Europe—which go for ludicrous sums. For those of us on a freelance budget, we were sharing tents or small rooms for the same sum with which I lived in a rather nice Haussmannian apartment in Paris. The starting rates for a container were $80 a night; mediocre meals were $10. Me, I was on the rice-and-beans diet; $1 a pop. Hand-washing laundry in water fresh from the Nile, I was reminded that this is indeed one of Africa’s least developed regions, despite the oases of luxury afforded to NGO, UN and media workers.

The story—the birth of a nation, or a variant thereupon—is strong. In the five decades following independence from British colonisation, the north & south were engaged in civil war for all but 11 years. That ended in 2005 with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which included the right to self-determination; the reason that we all find ourself here in January 2011.

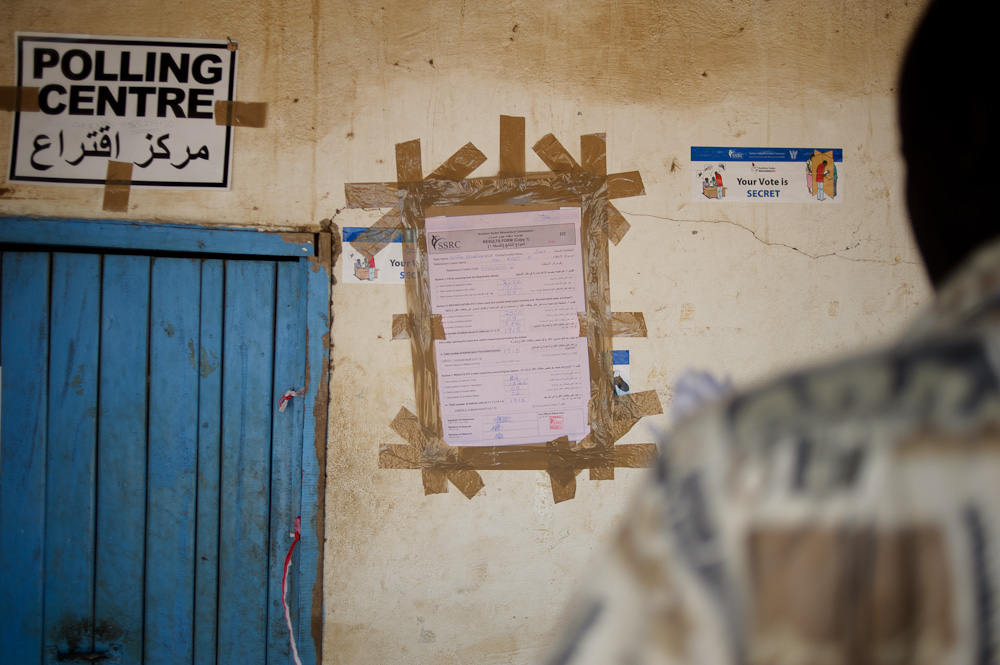

The act itself, though, is not the most scintillating of events. Three million people putting a ballot in a box. The first day, full of colour, was quite a spectacle. Queues had already formed at sunrise; traditional dance troops & joyous voters filled the grounds of the primary voting station in Africa’s soon-to-be newest capital. But following that, what was there really to cover? We engaged in feature stories, capitalising on the media spot-light for Sudan to cover other issues. A seasoned war-photographer with whom I was acquainted was bored out of his mind. “This story is fucking dead.” The clashes or unrest that some predicted, did not arrive. And happily so for the Sudanese.

What’s more, a senator in the US was shot, Tunisia ousted its president, and Australia was ravaged by floods. The calm pace of the “final walk to freedom” was lost in the chaos.

Now, the circus is packing up its tents and leaving. Many will be in Uganda for the forthcoming elections. But come July 9th, the day of independence, Juba will be buzzing again. The beer flowing to the agency expense accounts.