M23 rebels have increased the ground they hold in Rutshuru territory in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo. From the hills of Runyonyi, where conflict raged last month, the rebels took Bunagana on Friday (July 6th) before moving down to Rutshuru Centre. They have now withdrawn from Rutshuru Centre and other towns they briefly held, but the risk of a march on Goma—the provincial capital—looms in the air.

The United Nations and Congolese army (FARDC) have deployed a dozen or so tanks in the stretch of land bordering the Virunga National Park between Goma and Kibumba, a small town some 25km from the city.

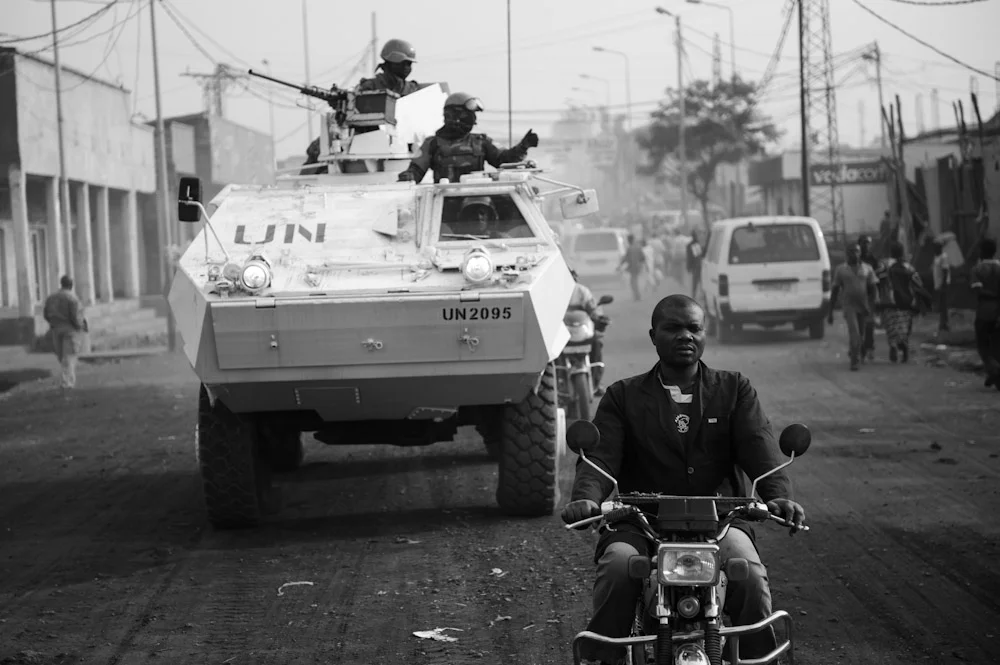

In Goma itself, peacekeepers have stepped up their “domination patrols” in an effort to reassure the population of their presence and commitment to keep the rebels far from the city. On the rim of a small, extinct volcano just at the edge of Goma’s wooden shacks, Indian peacekeepers are digging fox-holes for positions that will be “the last line of defence” before the city. “We have a clear view to the western flank” says the commanding officer there, gesturing towards the bush that extends to the base of the nearby Nyiragongo volcano. Below him as he talks, locals work on a patchwork of cultivated verdure, seemingly nonplussed by their new, foreign neighbours.

Last Wednesday (July 11th), Brigadier-General Harinder Singh (the UN brigade commander for North Kivu) met with General Lucien Bahuma who had arrived in Goma just the day before to command the FARDC’s 8th sector - the troubled North Kivu. Their strategy meeting was held on a hilltop overlooking UN tanks, just outside of Kibumba. Back in May, towards the end of the first ceasefire, thousands had fled Kibumba towards Goma when M23 first popped up on this side of the National Park. Coordination between the FARDC and M23 was the aim of the meeting, ensuring that no flanks were left open for the rebels to reach the city. Brig. Gen. Singh spoke of the need to learn from mistakes made in Bunagana when the rebels overran the strategic town on the Ugandan border. The UN seemingly weren’t sure who was FARDC and who was M23 after the government army strayed from their sector.

I couldn’t help but think back to May 19th, when Lieutenant-General Chander Prakash, the UN Force Commander for Congo, flew into Bunagana to the sound of heavy shelling and gunfire echoing out just down the hill, a few kilometres from the town. He stood in a patch of open ground, two Cheetah helicopters posed on the grass behind him, and addressed a crowd of local residents saying that the UN would absolutely not let Bunagana fall. Less than a month later, FARDC troops had fled across the border to Uganda, and one Indian peacekeeper had lost his life. M23 took control of the city.

The UN and FARDC launched helicopter strikes on M23 positions on Thursday and, reportedly, Friday, although the rebels claim they had little success. What it has provoked, though, is a letter sent by the new political wing of the group to the president of the UN Security Council in New York, asking if the UN has “changed its mandate to become an offensive and hostile force”, which they say would cause them to instruct their forces to put themselves in a defensive position against the UN contingents. “It is surprising that MONUSCO [the UN mission in Congo], considered as a neutral force for maintaining peace, chooses this moment to conduct an air-raid on the withdrawn and harmless positions of M23 further than 70km from the city of Goma.”

Overall, the chances of Goma falling are slim, and for now, few believe that M23 would march on the city. The rebels say that they have no intention to take Goma, although they would march on the city if attacks on Tutsis there continued. On Monday Rwandan students in Goma were escorted to the border for their protection with reports indicating that they had been attacked by an anti-Tutsi mob. Anti-Tutsi sentiment, however, does not seem obvious in the city.

The people of Goma seem unfazed by the armoured personnel carriers patrolling the streets and standing on intersections. If a fear of attack exists, it is not present in the throngs of people flocking to the markets and plying the rocky streets. Amidst the usual chaos of the city, a calm prevails here, despite the rebels occupying positions some 30km from Goma’s edge.