Soldiers with a Somali militia sit in their technical behind the rotting carcasses of cattle, just outside the Somali border town of Dhobley, just five kilometres from the Kenyan border. When surface water catchments dried out in the area, pastoralists brought their cattle to Dhobley for water from the town's two boreholes. But with only pumped water available, there was no grass for the cattle to graze upon, starving them to death.

Some of the first effects of the drought were the loss of livestock and failed harvests, with many families losing their entire livelihood.

Sheikh Abdulahi Abdiyow Barkem from Buur in Somalia's Galguduud district, lost his entire herd of 37 cattle and 90 goats to the drought. Left without livelihood, he came to Mogadishu, despite the conflict, and is now living in an IDP camp in the city.

Much of Somalia's population live in houses made of branches and rag coverings in rural parts of the country. Arriving at refugee camps such as Kenya's Dadaab refugee complex, they build similar shelters from the surrounding land. With Dadaab at over four times its planned capacity, new arrivals are building makeshift homes on the outskirts of the camp, where there is no infrastructure and few services.

For those coming to Mogadishu, it is often their first time in a city, and is a place of everyday conflict. The streets are roamed by freelance militia, extorting money where they can, and a constant battle rages between the African Union/Transitional Federal Government forces and opposition group Al-Shabaab.

An emaciated cow grazes on trash in Mogadishu's Hamarwayne district. Hamarwayne used to be one of the busiest areas of the city, with this site being the former gold souq.

Sa'cdiya Al Nur with her one and a half year old son, Hussein. They left their home in Bay region due to the drought, coming to Mogadishu in hope of humanitarian assistance. Hussein is suffering from severe acute malnutrition, and NGO staff here fear he may die tomorrow, or after tomorrow. "He is too weak to even brush away the flies" says an aid worker, one of very few working here.

"Before the drought, we had nothing, now we still have nothing" says Sa'cdiya, at a loss for what she to save her child.

A child stands in waters following the previous night's rains outside the Viishio Governo IDP camp in Mogadishu. With the rainy season approaching, and no sanitation in the camp, water-borne diseases now become a risk in the camp -- a twisted irony of the drought they originally fled.

Mothers queue with their children for health care given by Concern Worldwide staff at the Viishio Governo IDP camp in Mogadishu. With no sanitation in the camp, and with little food, the health levels are dire. Staff here were distributing zinc tablets for diarrhoea, de-worming tables, pain-killers and oral rehydration solution.

Many Somalis have nothing left. One year old Idman Mohamed, suffering from malnutrition and malaria, sits in his mother's lap at a compound for internally displaced persons in the Somali border town of Dhobley.

Idman's parents have left their home and walked for three days to reach Dhobley, in the hope of finding humanitarian assistance. Yet none is here. They say they have no money to buy any medicine for their son, and so intend to cross the border into Kenya.

A woman collects water to transport back to her home by camel in the Somali border town of Dhobley. The town has just two boreholes for approximately 5000 households, and many of those fleeing from all over South-Central Somalia have passed through Dhobley on their way to Kenya's Dadaab refugee camp, further straining the resources for an already weakened community.

Three families walk the long, dusty road from the Kenyan border with Somalia near Liboi, on their way to the Dadaab refugee camp. They have been walking for over two weeks, and still have several days ahead of them.

Three year-old Sadiya Ali and her mother crossed the Somali-Kenyan border with the rest of their family. Carrying very few belongings on a donkey cart, they are hoping to reach the Kenyan refugee camp of Dadaab - the biggest in the world. There is still around 100km of dusty road ahead of them.

This group of seven men left their home in Dinsour, Somalia, fifteen days previously, and are walking to Kenya's Dadaab refugee complex. Their families have already made the journey, and they are hoping to be reunited with them, in one of the three camps that now house over 380,000 people. Here, they stand on the sand-road for this photograph, just half an hour after having crossed the Kenyan border, with still around 100km to walk before Dadaab.

Hassan Ali prays by the road-side as he walks from the Somali-Kenyan border, just 2km away. Having walked for fifteen days with six other men, the only thing he is carrying with him is a small jug of water.

A young boy waits at the fence of a reception centre in Dagahaley camp in Kenya's Dadaab refugee complex. Originally built for 90,000 people, the camp now houses somewhere in the region of 380,000 refugees. After exhausting journeys, sometimes walking for two to three weeks, they then wait as large crowds try to access the centre.

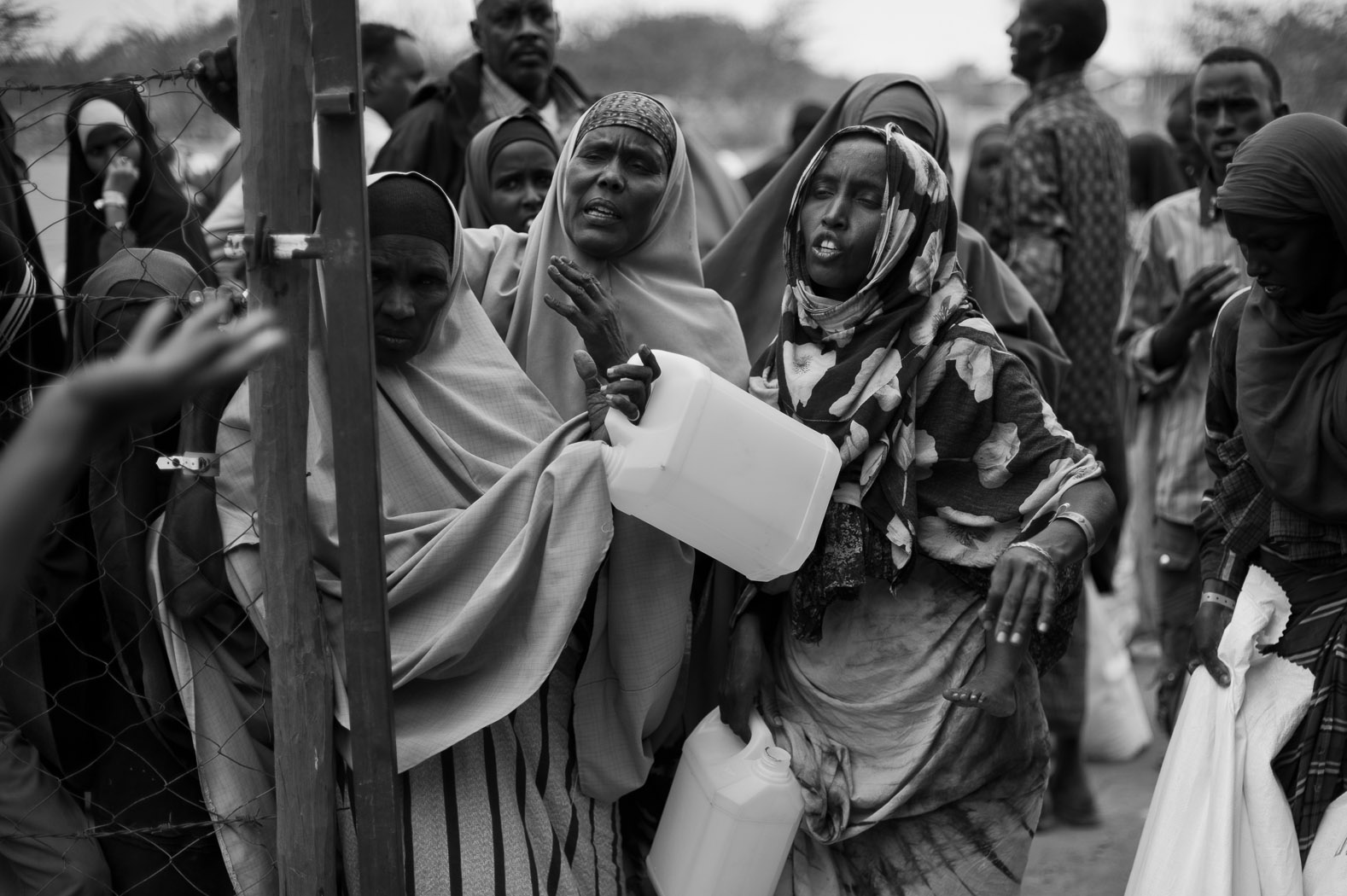

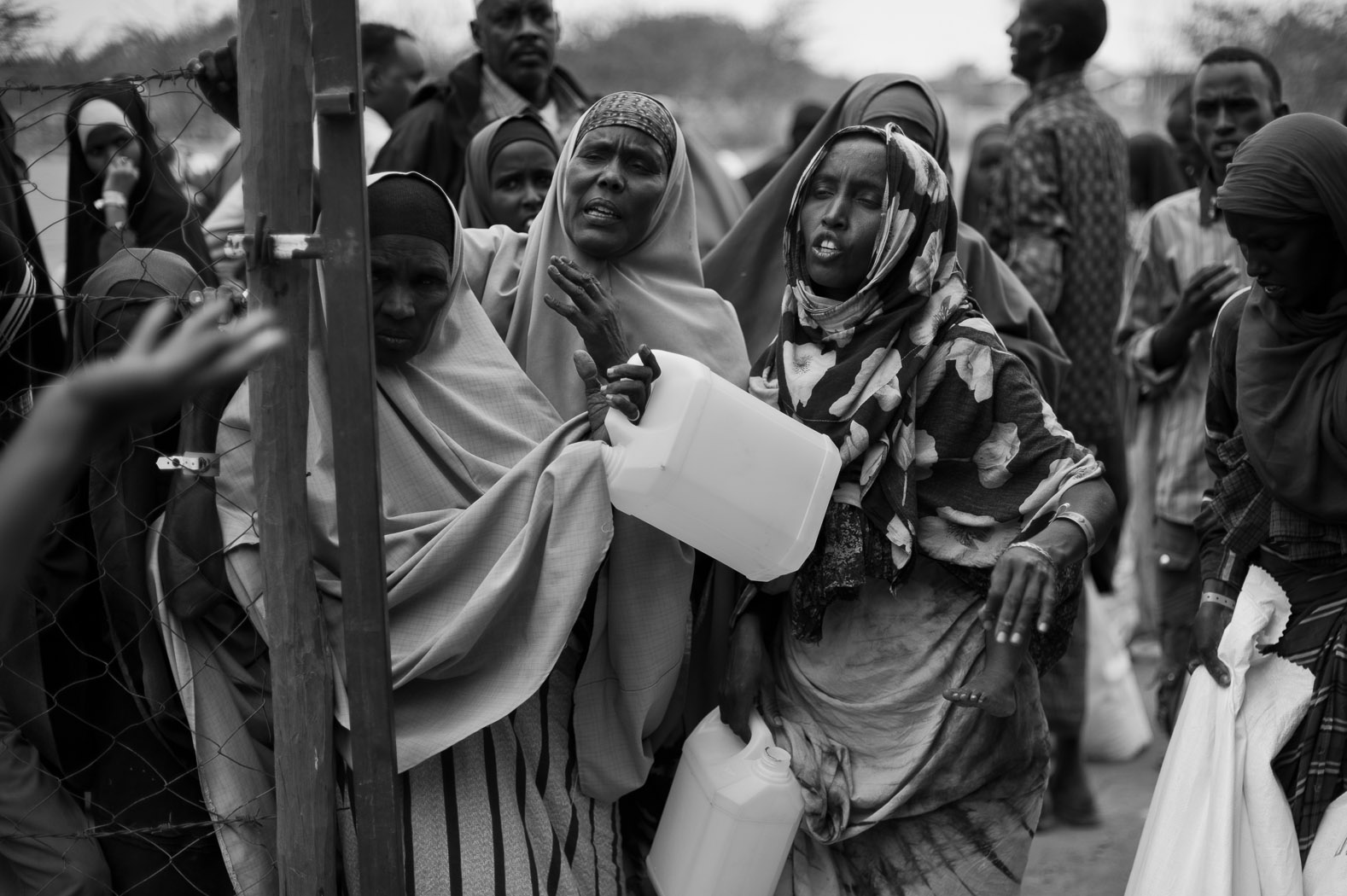

Somali women try to get access to water at the reception centre in Ifo camp. Having passed through the reception centre, refugees must wait to become registered in order to receive their ration-card and to officially assume the status of refugees. With so many new arrivals, however, there is currently a backlog of around two months, meaning that many people are without food once their initial ten-day ration has been consumed.

A newly arrived refugee has her fingerprint scanned as she and her family registers at a reception centre in Dagahaley camp in Kenya's Dadaab refugee complex. This is the first step in the long process of becoming a refugee in Dadaab, and screens against double-registrations.

Mothers wait at a Médicins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) health outpost on the outskirts of Dagahaley Refugee Camp.

A woman drags sacks of her monthly food ration from a food distribution centre in Dagahaley Refugee Camp. Aid agencies are struggling to meet the needs of the nearly four-hundred thousand refugees now living in Dadaab, where they see around 1300 new arrivals each day. Monthly rations include flour, pulses, salt and cooking oil.

The Marsabit region used to be known as the bread-basket of Kenya; as little as twenty years ago, there used to be large areas of forest here, and plentiful rain. The landscape today is arid scrubland, where animals now compete with humans for any available water, which is having to be trucked in from distant water sources.

Helema Guy (left) and Kula Roba (right) have lost almost all of their livestock through the drought. Living close to Marsabit, they say that the rains have failed here for several years.

Helema will sell one of her few remaining goats, today, to an NGO "livestock off take" programme, where they will receive money for the animal, as well as the meat, to share amongst two other households.

A Somali child suffering from acute malnutrition is weighed at the Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospital in Dagahaley refugee camp. MSF is currently treating over 7000 children for malnutrition in Dagahaley alone.

A Somali child suffering from severe acute malnutrition sits in a ward at the Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospital in Dagahaley refugee camp. Estimates for the number of children suffering from malnutrition in the outskirts of Dagahaley are over 40%.

In the Korogocho slum of Nairobi, Kenya, another side of the drought can be seen. Whilst food is available in the markets here, the huge impact that failed rains have had on the price of food, exacerbated by a global and regional fuel crisis, has pushed many families to the brink.

Rosemary Auma and her daughter, Millicent Mukundi, stand in the yard of their home in the slums. Millicent is suffering from malnutrition; Rosemary says that with only casual work for her and her husband, it is difficult for her family to have more than one meal a day.

"Life is much harder in the city, if there is no work you won’t eat", she says.

Irene Adhiambo used to work on the dump-site in Nairobi, scavenging for food to feed her family, and scraps to sell to earn a livelihood. Living in Korogocho slum, the effects of the drought have pushed up food prices in urban areas, causing problems for the urban poor. "Last year, things were a bit better, but this year, things are really hard" she says.

Now enrolled in an NGO's livelihoods programme, Irene says "if God can help me, I'll see if I'll be able to stand with my life."

The religious posters and icons covering the walls of her home in the slums were all found at the dump site.