Sudanese Elections Run-up

Sudan, 1989: General Omar Hasan Ahmad al-Bashir leads a military coup, ousting the civilian regime, suspending political parties and naming himself Chief of State, Prime Minister, Chief of the Armed Forces and Minister of Defence. Four years later, he appoints himself President and disbands rival political parties.

In 1996, President Bashir transformed the country into an Islamic totalitarian single-party state, and in the national election of that year, he was the only candidate to run. Attempts to reduce the President’s power before the 2000 election resulted in Bashir dissolving parliament and declaring a state of emergency. Opposition parties boycotted these elections.

Come 2005, civil war was officially ended in Sudan with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), and the creation of a co-Vice President, representing the South, formed part of the new Government of National Unity.

Now, in April 2010, Sudan is preparing itself for what are heralded as the “first genuine multi-party poll in the country since 1986”. Ahead of the southern secession referendum, scheduled for January 2011, the elections are seen as a test of the country’s democratic ability. Al-Bashir, who’s victory is widely quoted as “assured”, is also aiming to legitimise his presidency following last year’s indictment by the International Criminal Court, facing charges for seven counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

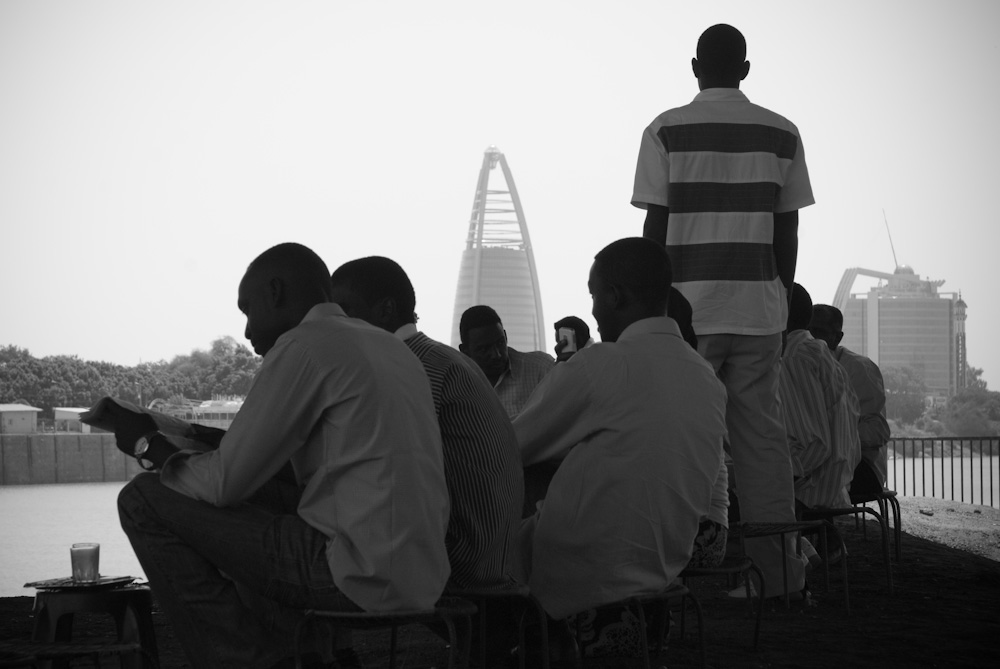

Walking the streets of Khartoum, political posters line every street. Amongst these, there is a marked difference in the means available to garner votes; traveling down from the northern border to Khartoum, the route is lined by giant billboards showing al-Bashir against a backdrop of new roads, bridges and dams, projects instigated under his National Congress Party’s (NCP) rule. Apart from the odd billboard for the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), the ruling party in the South, opposition posters are somewhat marginalised, furtively pasted to walls, torn at the edges.

The elections are already mired by condemnations from both international observers and opposition parties. Human-Rights Watch alleges repression of opponents of the NCP, as well as media restrictions, claiming it threatens the prospect of a “free, fair and credible vote”. Darfur is still torn by conflict, the International Crisis Group (ICG) saying many displaced Darfuris will be denied the right to cast their vote. Around 2.6 million people live in displaced persons’ camps. Despite this, the National Electoral Commission says that 81% of eligible voters have been registered. Yet the ICG claims that the NCP has “has manipulated the census results and voter registration, drafted the election laws in its favour, gerrymandered electoral districts, co-opted traditional leaders and bought tribal loyalties”.

The European Union has withdrawn its election observers from Darfur, citing safety concerns. Some foreign election observers have recommended a postponement of the vote in order to resolve the issues of fraud, logistics and security, resulting in a fiery condemnation from the President.

Any foreigner or organisation that demands the delay of elections will be expelled sooner rather than later … We want them to observe the elections, but if they interfere in our affairs and demand the delay, we will cut off their fingers and put them under our shoes and expel them.

— Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s incumbent president

The problems have contributed to stories emerging of many opposition parties boycotting the elections. Conflicting stories of party boycotts have appeared in both the national and international press, leading to confusion amongst voters. Here in Khartoum, I have read articles in the same newspaper providing contradictory information. The international media says that Yasir Arman of the SPLM has withdrawn from the presidential race citing alleged fraud and the instability in Western Darfur; he was expected to provide the greatest challenge to the Bashir’s presidency in the North. The SPLM itself is withdrawing from several northern states. The northern Umma party is said to have withdrawn from the poll completely.

Whilst the international media talks of the wide-spread opposition to Bashir, here in the north, many people say they will vote for him. Several people I spoke to in Karima said that whilst they believed he & the NCP have many problems — corruption and the violence in Darfur, for example — they think he is the strongest candidate to lead the country. “He has so much more experience than the others.” Others believe the boycott by candidates exemplifies their lack of qualities for president. Disillusion also plays its part, the BBC quotes a first-time voter as saying “I don’t have any options, because all the people I could have voted for have withdrawn, they are cowards!”

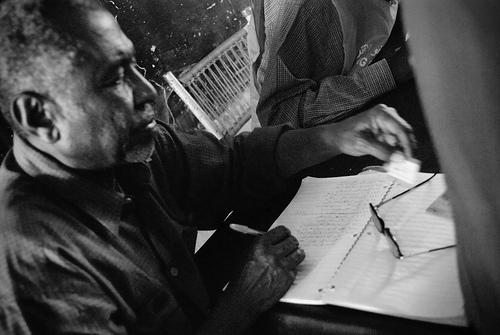

The Sudanese also face confusion about the logistics involved during the three days of polling which begin on April 11. Many are unsure if there will be a national holiday and if public transport, vital for some to reach polling stations, will be operating. Bus tickets out of Khartoum have seen a price increase, preventing some from making the journey home to where they are registered.

All of this comes before a single vote has been cast. Talking with other internationals here, uncertainty is the word on everybody’s lips. This is the first time in over two decades that such an event has taken place, and nobody knows how it will pan out. The UK Foreign Office website warns “as a precaution in case of any rallies or demonstrations which might inhibit movement, you are advised to maintain several days’ stock of food and water”. Me, I’ll be staying in Khartoum for a few days longer…

» More photos: 2010 Sudanese elections.