St. Joseph’s VTC

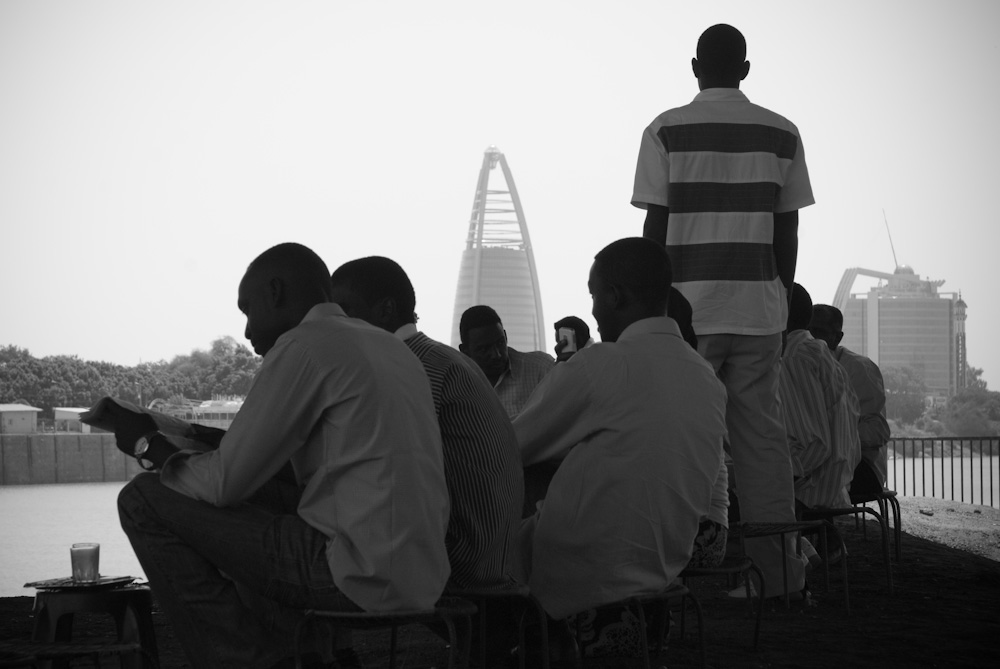

Behind a large, steel gate off a dusty street in Khartoum 3 lies St. Joseph’s Vocational Training Centre, a school whose students are largely made up of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from Southern Sudan. Four trucks pass through these gates every morning, bringing the students from their IDP camps which lie on the outskirts of Northern Sudan’s capital.

I visited the school with a friend who works for VIS (Volontariato Internazionale per lo Sviluppo), an Italian NGO that has written the Y.E.S. project — Youth Empowerment in Sudan. The Y.E.S. project is implemented by the Salesians of Don Bosco, a Roman Catholic religious order working largely with the young and the poor, and posters of Saint John Bosco are dotted around the school. Whilst many of the students are Christian, religious instruction is not part of their work here, and Muslim students are given equal opportunity to pray.

Southern Sudan has been racked by nearly forty years of civil war with the North, the second war running from 1983, ended by the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). It is estimated that more than 4 million of the South’s civilians were forced to flee their homes, many of whom now live in or around Khartoum. With the signing of the CPA, several objectives were defined, including the forthcoming referendum for the independence of the South, scheduled for January 2011. Part of the work of VIS, through the Salesians, is to support & aid the graduated students who are interested in returning to the South, through cooperation with international agencies such as the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

Much of the funding for the work here comes from the European Commission through the FOOD budget-line, and part of the work of VIS is to provide a more nourishing meal to the students here. As I saw bread & fuul handed out, it was explained that for many of these students, this is their only meal of the day; this Sudanese staple has been supplemented by other food groups, trying to improve the diet of the students.

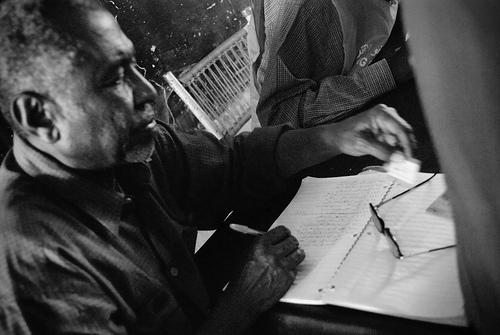

Several classrooms-cum-workshops surround the dusty recreational area, inside of which I found students studying subjects varying from car-mechanics to carpentry. Inside the graphic design & printing workshop, the guys were particularly keen to pose whilst leaning over the huge printing presses. To supplement the income of the school, much of the students’ work is sold in varying applications, from designing business cards, building furniture and repairing cars. The progression of this is vital if the school will become self-sufficient once the NGO funding ends in June 2011.

» More photos here: St. Joseph’s VTC.