The Problems Facing a Postman

The address on the envelope was a series of street names—written in Arabic, narrowing down from the main road to smaller lanes. This was not going to be an easy task — we were without a map, and in any case, here in Sudan, street names aren’t a common occurrence. People know roads by the district they are in and by directions, not by name. Often when taking a rickshaw home, saying the name of even a major thoroughfare would draw blank looks from the driver.

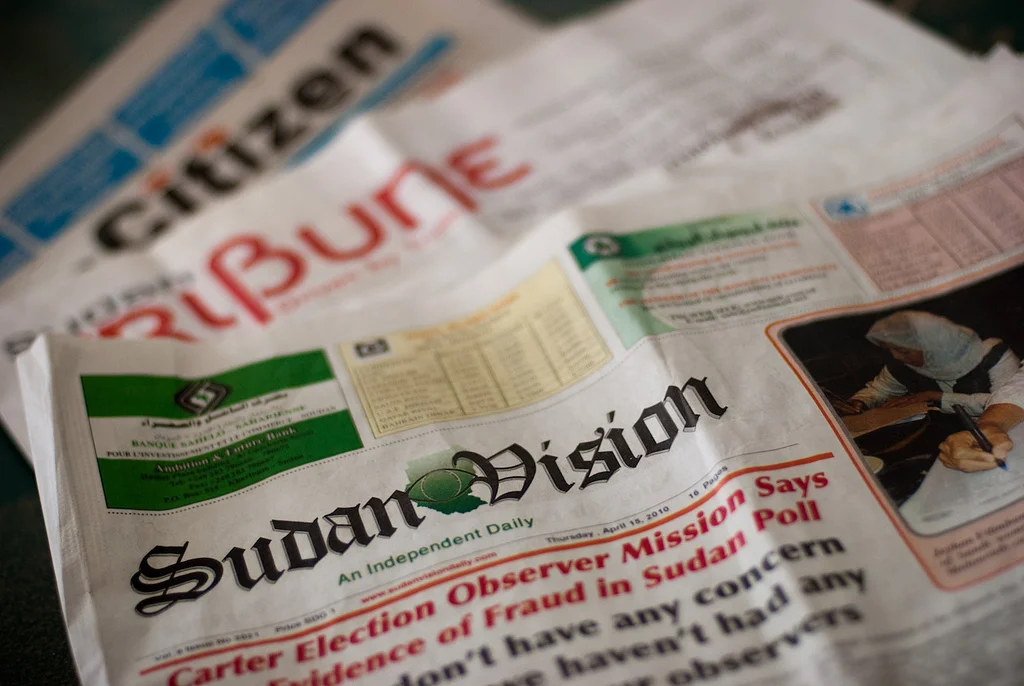

So here we stood in Omdurman, bearing a letter of someone who had visited Sudan six years ago and who had entrusted it to a friend working in Sudan to deliver. With embargoes, sanctions and the state of the Sudanese postal service, popping a stamp on the envelope makes post a less viable option than back home.

Asking around, people gave us blank or puzzled looks as we tried to explain the address in broken Arabic. “Where does your friend live?” we would be asked as we showed the envelope. “We were hoping this address would tell us” we thought, silently. At times, this lead to an uncomfortable moment when we realised that the person to whom we were showing this letter could not read the address. Illiteracy rates in Sudan are somewhere around 39%.

Another problem facing those with questions in Sudan is that no-one will ever simply say “sorry, I don’t know”. If looking for something and the person doesn’t know it, there will be a hesitation and then vague pointing in some direction. After some time wandering the streets of Khartoum, I came to realise that the length of the pause dictates the surety of a reply. More than a couple of seconds, and the response can be dismissed completely.

In the baking sun, walking off the main road following directions from a man exuding confidence and without pause, we felt as though we were getting somewhere. A group of men were stood outside a shop, welding together bedsteads on the street side. Another was weaving colourful cord forming the base of the bed, a style popular amongst the lokandas of my journey to Khartoum.

A debate ensued about in which direction our sought-after road lay. I couldn’t follow it all, but at one point three men were all pointing in completely opposite ways. Following the route of the wisest looking man, we asked at the next junction, at which point we were directed back in the way we just came. Flagging down rickshaw drivers drew more blank looks.

When we finally found a tuk-tuk that seemed confident he could render us to our desired location, we jumped in, speeding through the dusty, potholed streets of Omdurman. He knocked on the steel gate to a large house, and a slit opened, the eye of a veiled girl was perceivable as she hid behind the doorway. When her father came out, he knocked on his neighbour’s door and they tried to decipher the address. Perhaps our tuk-tuk driver was confident he knew somebody who would know where the house was located. And “no, we don’t have their phone number…”

We soon found ourself back in the rickshaw, driving back across town. Evidently not pressed for time, we stopped at the driver’s favourite tea-lady, an Ethiopian with whom he flirted outrageously, before once-again entering the labyrinth of Omdurman’s smaller lanes.

Children in the street wondered what these two khawaaja were doing here, and intimated that our addressee had moved to El-Obeid, a city seven hour’s drive from here; or perhaps he was just away on business. More gates were knocked, and a woman came out of a house, saying she knew the guy, and perhaps even our sender. “The French man, yes I remember him.”

Handing over the envelope, we were not sure if we had really accomplished our mission or not. The insha’Allah factor would play a big part in this envelope finding its way from sender to receiver, six years after their acquaintance.

I wouldn’t want to be a postie here.